- From our Sponsors -

A startup is like a box. A very special box.

The box has a value. Its value increases as you put more things in the box. Add a patent and the value increases. Add a kick-ass management team, the value increases. Easy, right?

The box is also magical. When you put US$1 inside, it will return you US$2, US$3, or even US$10. Amazing!

The problem is that building a box can be very expensive. So, you need to go and see people with money (let’s call them investors) and offer them a deal that sounds a bit like this: “Give me US$1 million to build a box, and you’ll get X percent of everything that comes out of it.”

But how much should X be?

It depends on the pre-money valuation, i.e. the value of the box at the moment of the investment. But calculating the it is tricky. This article will take you through nine different valuation methods to help you better understand how to determine pre-money valuation.

Please note that most valuation methods are based on data such as comparables or base valuations. How to find such data is an issue per se and will not be addressed in this article (but most likely in the future).

The Berkus Method is a simple and convenient rule of thumb to estimate the value of your box. It was designed by Dave Berkus, a renowned author and business angel investor. The starting point is this: Do you believe that the box can reach US$20 million in revenue by the fifth year of business? If the answer is yes, you can assess your box against the five key criteria for building boxes.

This will give you a rough idea of how much your box is worth (aka pre-money valuation) and, more importantly, what you should improve. Note that according to Berkus, the pre-money valuation should not be more than US$2 million.

The Berkus Method is meant for pre-revenue startups. To read more about the Berkus Method, go here.

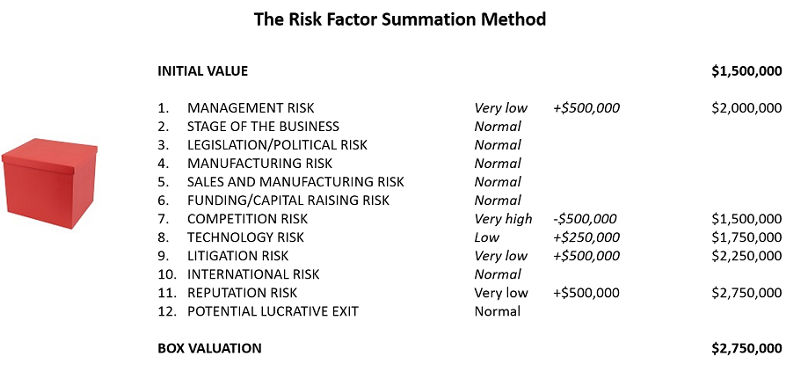

The Risk Factor Summation Method or RFS Method is a slightly more evolved version of the Berkus Method. First, you determine an initial value for your box. Then, you adjust the said value for 12 risk factors inherent to box-building.

The initial value is determined as the average value for a similar box in your area and risk factors are modeled as multiples of US$250,000, ranging from US$500,000 for a very low risk to below US$500,000 for a very high risk. The most difficult part here, and in most valuation methods, is actually finding data about similar boxes.

The RFS Method is meant for pre-revenue startups. To learn more about it, read this.

The Scorecard Valuation Method is a more elaborate approach to the box valuation problem. It starts the same way as the RFS method, i.e. you determine a base valuation for your box, then you adjust the value for a certain set of criteria. Nothing new, except that those criteria are themselves weighed based on their impact on the overall success of the project.

This method can also be found under the name of Bill Payne Method, which considers six criteria: management (30 percent), size of opportunity (25 percent), product or service (10 percent), sales channels (10 percent), stage of business (10 percent), and other factors (15 percent).

The Scorecard Valuation Method is meant for pre-revenue startups. To read more about it, click here.

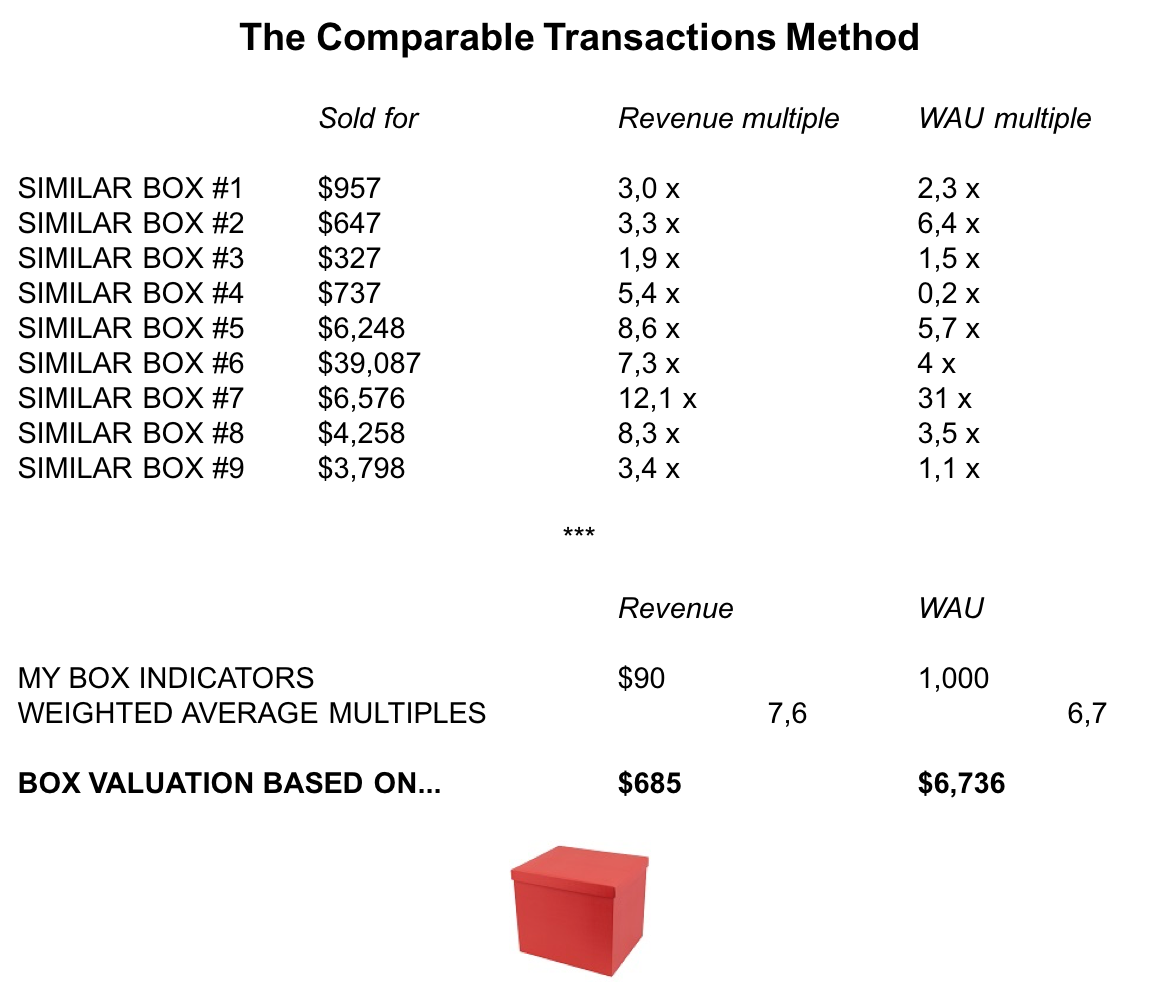

The Comparable Transactions Method is really just a rule of three.

Depending on the type of box you are building, you want to find an indicator that will be a good proxy for the value of your box. This indicator can be specific to your industry: monthly recurring revenue (SaaS), HR headcount (interim), number of outlets (retail), patent filed (medtech/biotech), weekly active users or WAU (messengers), etc. Most of the time, you can just take lines from the P&L: sales, gross margin, EBITDA, etc.

The Comparable Transactions Method is meant for pre- and post-revenue startups. To read more about it, click here.

Forget about how magical the box is and see how much one pound of cardboard is worth.

The book value refers to the net worth of the company, i.e. the tangible assets of the box, the “hard parts.”

The Book Value Method is particularly irrelevant for startups as it is focused on the “tangible” value of the company, while most startups focus on intangible assets: R&D for a biotech firm, user base and software development for a web startup, etc.

To read more about the Book Value method, click here.

Rarely good from a seller perspective, the liquidation value is, as implied by its name, the valuation you apply to a company when it is going out of business.

Things that count for a liquidation value estimation are all the tangible assets: real estate, equipment, inventory, everything you can find a buyer for in a short span of time.

The mindset is this: If I sell whatever the company can in less than two months, how much money will that make? All the intangibles, on the other hand, are considered worthless in a liquidation process (the underlying assumption is that if it was worth something, it would have already been sold at the time you enter in liquidation): patents, copyright, and any other intellectual property.

Practically, the liquidation value is the sum of the scrap value of all the tangible assets of the company.

For an investor, the liquidation value is useful as a parameter to evaluate the risk of the investment. A higher potential liquidation value means a lower risk. For example, all other things equal, it is preferable to invest in a company that owns its equipment compared to one that leases it. If everything goes wrong and you go out of business, at least you can get some money selling the equipment, whereas nothing if you lease it.

So, what is the difference between book value and liquidation value? If a startup really had to sell its assets in the case of a bankruptcy, the value it would get from the sale would likely be below its book value due to the adverse conditions of the sales.

So, liquidation value < book value. Although they both account for tangible assets, the context in which those assets are valued differs. As Ben Graham points out, the liquidation value measures what the stockholders could get out of the business, while the book value measures what they have put into the business.

If your box works well, it brings in a certain amount of cash every year. Consequently, you could say that the current value of the box is the sum of all the future cash flows over the next years. And that is exactly the reasoning behind the DCF method.

Let’s say you are projecting cash flows over N years. What will happen after that? This is the question addressed by the terminal value (TV).

You consider the business will keep growing at a steady pace and generating indefinite cash flows after N years. You can then apply the formula for TV:

TV = CFn+1/(r- g); where “r” is the discount rate and “g” is the expected growth rate.

You consider an exit after the N years. First, you want to estimate the future value of the acquisition, for example with the comparable method transaction (see above). Then, you have to discount this future value to get its net present value.

TV = exit value/(1+r)^n

Although technically, you could use it for post-revenue startups, it is just not meant for startup valuation. To read more about the DCF method, click here.

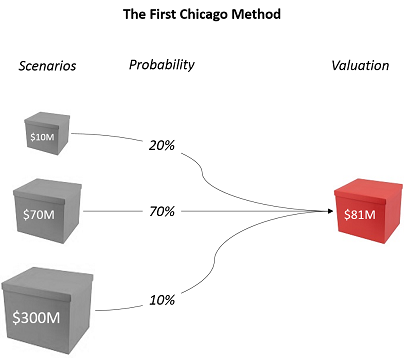

The First Chicago Method answers to a specific situation: what if your box has a small chance of becoming huge? How can you assess this potential?

The First Chicago Method (named after the late First Chicago Bank) deals with this issue by making three valuations: a worst case scenario (tiny box), a normal case scenario (normal box), a best case scenario (big box).

Each valuation is made with the DCF Method (or, if not possible, with the internal rate of return formula or with multiples). You then decide on a percentage reflecting the probability of each scenario to happen. Your valuation, according to the First Chicago Method, is the weighted average of each case.

The First Chicago Method is meant for post-revenue startups. You can read more about it here.

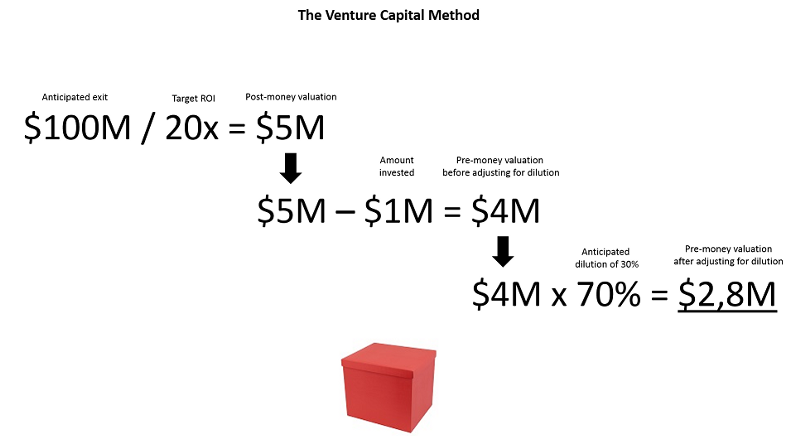

As its name indicates, the Venture Capital Method stands from the viewpoint of the investor.

An investor always looks for a specific return on investment, say 20 times. Besides, according to industry standards, an investor thinks that your box could be sold for US$100 million in eight years.

Based on those two elements, an investor can easily determine the maximum price he or she is willing to pay for investing in your box after adjusting for dilution.

The Venture Capital Method is meant for pre- and post-revenue startups. To read more about the it, click here.

Congratulations! If you made it this far, you know nine valuation methods. So, you must be screaming from the inside, “What is the best valuation method?”

First, keep in mind that the only methods really used by VCs are comparables and a rough estimate of how much dilution is acceptable by the founders.

For example, giving out 15 to 25 percent for a seed round comprised between around US$334,000 and US$556,000, or making sure that the founders remain majority shareholders after a series A.

Second, let us remember that valuations are nothing but formalized guesstimates. Valuations never show the true value of your company. They just show two things: (1) how bad the market is willing to invest in your little red box and (2) how bad you are willing to accept it.

Having said that, I find that the best valuation method is the one described by Pierre Entremont, early-stage investor at Otium Capital, in this excellent article. According to him, you should start from defining your needs and then negotiate dilution. He wrote:

The optimal amount raised is the maximal amount which, in a given period, allows the last dollar raised to be more useful to the company than it is harmful to the entrepreneur.

Valuations are a good starting point when considering fundraising. They help build the reasoning behind the figures and objectify the discussion. But in the end, they are just the theoretical introduction to a more significant game of supply and demand.

We hope that you enjoyed reading this.

- From our Sponsors -